The Best Laid Plans

Design & Data Visualisation

A short piece about stumbling into the world of data visualisation and working on a data driven project that attempted to visualise the war in Yemen, diving into the process of collating and cleaning the data, creating a narrative, a visual language and eventually a dashboard.

Scroll to read below or read on Medium.

This piece is adapted from a talk I gave at Visualising Data London, Microsoft Reactor on 20th June, 2019.

I had an odd journey into data journalism. It goes something like this — Five years ago I was surrounded by boxes and wrapping up my role as a design consultant for Embarq, a sustainable transport and research lab in Bangalore. Four years ago I was at Windsor Castle looking at the Queen’s private collection of Persian Manuscripts — having taken a brief hiatus from design to do a masters in the history of art at The Courtauld specialising in Persian art. Three years ago I was living out of a suitcase and starting my first job in London at Small Media Foundation, a media and research lab working with civil society organisations in the Middle East. Two years ago — more boxes, more suitcases, more moves — but now I was helping organise a DATA4CHANGE workshop in Beirut for those uninitiated —DATA4CHANGE is a workshop which brings together designers and developers along with human rights organisations to create advocacy campaigns. And finally we come to one year ago when I was wrapping up a project with Yemen Peace Project and DATA4CHANGE working on Visualising Yemen’s Invisible War which is the project we launched in December last year. With that out of the way, I can get jump into the project, the processes involved, how it developed and the final output

The original idea of the project came out of a 2016 Beirut based DATA4CHANGE workshop, one that I had attended as a participant.

Cover image

Just to give some background — in 2015 The Yemeni president was overthrown in a coup and since then there has been an ongoing civil war between a regime backed by an international coalition led by Saudi Arabia with backing from the U.S. government against a north Yemeni militant group. If you really want all the details you can visit the project link — as I hope to explain, we’ve done some really nice stuff to make the data more accessible.

We worked with a dataset that recorded the volume of air-strikes in Yemen and the kind of sites that were targeted, where they were located and when they took place.

A screen grab of the data we were working with

The initial dataset, the one we worked with during the workshop in 2016 recorded airstrikes from March 2015 to August 2016 — that’s nearly eighteen months of endless air strikes across the entire country. Initially the project was quite slow to get off the ground. Following a lull after the 2016 workshop we resurrected the project in late 2017. The project was to create an interactive story that maps the airstrikes in three major cities in Yemen and video interviews of residents in collaboration with the original organisation who had brought the dataset.

But the project went through many embodiments. In March 2018 — six months into reviving the project our key partners — a journalist and filmmaker duo from Yemen — had to pull out due to personal reasons. Which was unfortunate for them and frustrating for us. This meant either axing the project. Again. Or rapidly finding a new partner, realigning with their timelines and objectives while ensuring work already done was not wasted whilst still giving them enough room to take creative leadership. No biggie.

Thankfully the departing organisation had left a bread crumb trail in emails and half-mentions that led us to a new partner fairly easily.

In September 2018 we partnered with a DC based advocacy organisation dedicated solely to Yemeni affairs and the US-Yemen relationship. This was a stroke of luck! It did mean though the entire idea of the project changed. . .

Meanwhile I had gone through a dozen rounds of updating the data, codifying it and cleaning it. In the early days I struggled to keep up with the rapidly updating dataset while managing the project.

The first ever dataset we got our hands on recorded the airstrikes from march 2015 to august 2016. When we resurrected the project in late 2017 — at that point — the dataset had grown to fifteen thousand eight hundred and forty six rows and detailed the airstrikes from march 2015 to December 2017 — that’s twenty-eight months of airstrike data. Then we got another updated version that recorded the air strikes till March 2018 — this meant we were working with thirty three months of airstrike data — that’s almost three years, you could have started and finished your undergraduate degree in that time — and tragically the conflict continued. While work on the project progressed the dataset was again updated to include records till August 2018 — so that’s another eight months — that’s an internship! In December 2018 when we published the story the data had eighteen thousand seven hundred and fourteen rows and recorded the airstrikes till November 5 2018. This means the final story was around six weeks shy of real time data.

To supplement the datasets me and some colleagues scraped the geospatial coordinates for the governorates as well as the last recorded population. This meant we could now locate the air strike data on a map over three years. In all honesty we could possibly have stopped then… that in itself was a compelling story. But we didn’t.

I then located and added satellite imagery of specific sites that had been bombed.

This was an important visual to remind us as well as the user that the numbers in the dataset are about real people and real places.

Sana’a International Airport

Whilst working on this and having partnered with Yemen Peace Project in September 2018 they told us that they would like to use this as a tool to lobby and inform representatives, readers and key decision makers in DC ahead of legislation being presented at both the house and senate that asks to put an end to the air campaign, or at least end US involvement in it. These motions were to take place between November and January. We very rapidly had a call to action and a looming deadline!

The false starts and ups and downs had ensured that at this stage I didn’t have visual identity for the project, or any substantial design work, let alone accurate visualisations.

If you haven’t noticed — I struggled with being the de facto dataset expert, managing the project while being the designer and working on the data visualisations. As a designer I’m used to starting a sentence with, ‘you know what will be a cool thing to try’ and waiting for the project manager to say ‘yeah… let’s try that but is it scalable, can we do it within the timeline, why did you use that font’… I had to have far too many of these conversations with myself and eventually it got a bit tiring — so if you thought this article might be about me showcasing some super cool hi tech visualisations, I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news — it’s me mainly griping about how difficult this was.

So at this stage, I had a chosen format — a long form story, I had a clean and up to date dataset, I had a call to action that asked its readers to write to their local representative demanding action on the legislation, a deadline obviously but I still was not entirely convinced with the data visualisations that I had tried so far and if any of them worked with the direction we had decided to go in.

I initially played around with RAW graphs — an open source data visualisation framework — and we had some interesting outputs which had a lot of potential.

Bee swarm graph

I used a bee swarm graph to plot air-strikes categorised by targets. I was very drawn to this visual and how the volume of air strikes was represented with the crowding of the dots.

Then I used a sankey diagram to show the governorates with a high number of airstrikes and which sites were targeted. With a bit of work there could have been a story in there but it wasn’t the most inspiring option.

Sankey graph

I also struggled with embedding these visualisations, and sorely missed the additional information that was hiding under each strand of the sankey diagram or each dot of the bee swarm. It was also all very slow and the dataset was far too heavy for this platform to be a viable option. Plus it was hardly something I could update every time the dataset added a new row.

This is when I remembered Tableau — I had barely used it — I was part-scared to use it! This was the first time in earnest I was using the beast that Tableau is and there was a steep learning curve. It didn’t help that I had quite a tight deadline — after the change in direction the whole project had to be up and running in 3 months — to be out before key legislation hit the senate.

I very quickly fell in love with Tableau. It was absolutely perfect for what we needed to visually achieve with our dataset. The opaque interface became my friend, the constant signing in to save a file, sure I could get used to that — all I had to do now was to rapidly create a visualisation that might help lobby senators and representatives to end the Yemeni war. No pressure.

I was most keen to try out the coordinate data we had scraped. Having struggled to initially merge that with the main dataset …

There are 21 governorates in Yemen and each of them has at least five different spellings. Slowly but surely I managed to line everything up with the right coordinate and imported the dataset into Tableau.

Now I wanted a map. So after importing the data, fiddled with some settings, the most basic ones I imagine and managed to create a playback of three years of airstrike data. The intensity of colour is how recent it was… fading into white, and the size of the circle representing the number of strikes in that particular location.

Screen grab of the map with air strike data being played

Then I tried a more classic timeline, where each dot was the number of airstrikes categorised by target type which were colour coded.

It was absolutely wonderful seeing it come to life — being able to interact with the data — but also terrifying every time I remember what that dataset was about.

I then used a treemap graph to see what types of buildings or areas had the highest volume of air raids. It’s quite good in telling me exactly that but it takes a lot of space to give not enough information. You also have to remember that many of the air strike targets are unknown and the minute you see unknown in a graph — interest wanes… but the number of unknown targets are so high that you surely can’t ignore them — it’s a fine balance getting that right…

The way the narrative was progressing it made sense for us to create a site where large amounts of data could be quickly accessed — a single page that could give an overview of the dataset while still providing specifics — something like this would be useful when talking to senators, representatives and other officials. We really needed to be able to get our message across quickly and efficiently — This is when I decided to create a dashboard.

This dashboard could be connected to a live sheet and be constantly updating — resolving the issue of the rapidly growing dataset. It would work to quickly give people specific numbers regarding, targets, number of air strikes and progression over the years. It could also be used to create dozens of stories, a starting point for anyone looking for information about the air-strikes in Yemen.

To get to the dashboard I went back to the timeline — the first version was in the right vein but I broke it down further.

I created a granular timeline where each day was visible, the size of each square representing the number of air raids that day and the colour indicating type of category.

The granular timeline

I decided that the dashboard would be embedded at the end of the piece — if somebody was reading the story they could select it from the navigation OR they would get their naturally if they didn’t lose interest. If it was being used to lobby specific individuals then even screen grabs of the right view would be useful to pique someone’s interest.

Within the narrative itself I wanted to include smaller bite sized graphics. These visualisations were largely two pages of content which I distilled and placed into excel which then allowed me to make two visualisations.

The first recorded the kind of arms and armaments sold by the U.S. and the financial gains involved with that.

This visual was important to show how lucrative the conflict in Yemen was for the U.S. economy and that it wasn’t just some naive misplaced trust in coalition leaders.

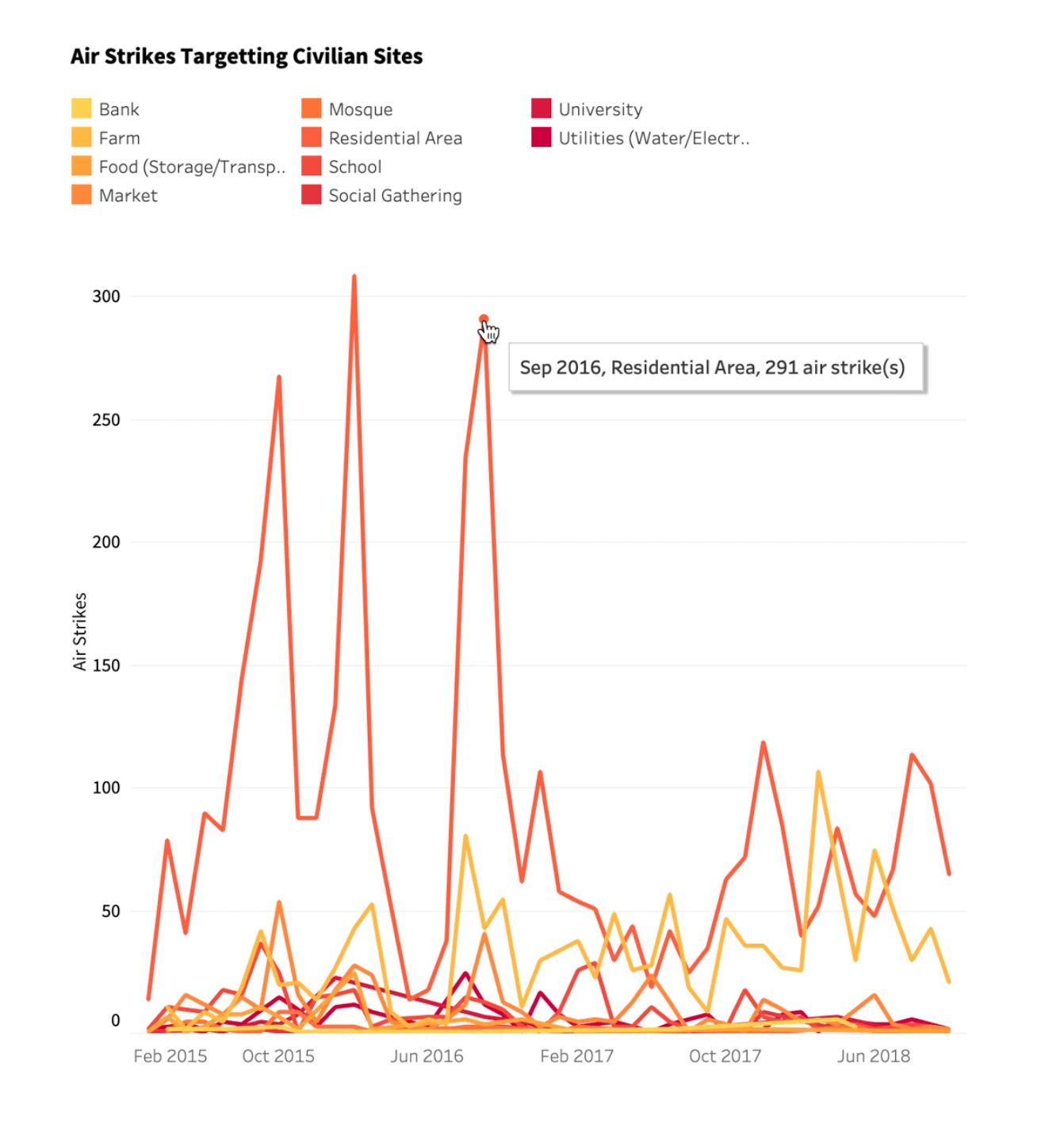

The second interactive graphic gave a more detailed view of the number of air strikes on civilian sites from 2015 to 2018, showing periods when the air raids were exceptionally aggressive.

With these two mini visualisations in the main content I could go back to the dashboard.

In the dashboard I included a summary number, added options where the user could select the year, filter by category, hover and get detailed information, highlight specific incidents while still getting an overview and then finally added annotations, not the most elegant kind but enough to add more context, highlighting specific events and moments which were covered in the press or when key decisions around the Yemen conflict were made.

Once we had a working dashboard I made a mobile and tablet version of the visualisation with relevant break points.

And we had a working story!!

The story was built on Shorthand, and once I managed to get enough of the data cleaned the visual language began to take shape.

The narrative was largely about U.S. policy towards Yemen and that detailed very much the visual language, graphics, colours, typeface and photographs…

In terms of how the situation has progressed since the campaign: in December 2018 the senate passed an important resolution to limit U.S. support to the Saudi coalition — this got through the House of Representatives in April of this year, but was then unfortunately, maybe predictably, blocked by Trump.

This piece is going to be a work in progress. Especially as the conflict continues.

You can view the dashboard on the tableau site here, and the story here.

If anyone would like access to the data or workbook feel free to get in touch!